Download Notebook

Contents

- Generating samples from N(0,1)

- Rejection Sampling Implementation

- Expectation values

- Expectations from Importance Sampling

- Some notes on variance

- A different importance sampling estimator

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import scipy as sp

import matplotlib as mpl

import matplotlib.cm as cm

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

pd.set_option('display.width', 500)

pd.set_option('display.max_columns', 100)

pd.set_option('display.notebook_repr_html', True)

import seaborn as sns

sns.set_style("whitegrid")

sns.set_context("poster")

Generating samples from N(0,1)

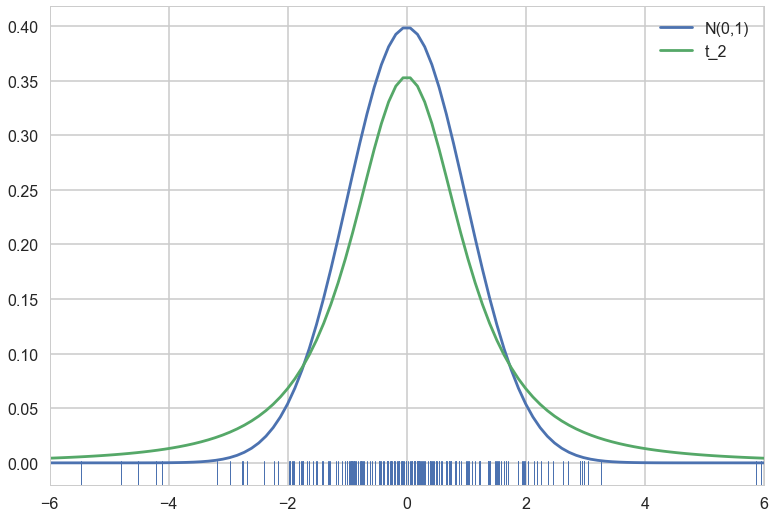

In what I call ny “fake-news” examples, we are going to generate samples from $N(0,1)$ using a t-distribution with 2 degrees of freedom to majorize it.

from scipy.stats import norm, t

n = norm()

t2 = t(2)

Here is a plot of the two distributions. Note that since the t has larger tails, it is shorter than the normal in the middle..we also make a rugplot of samples from the t, since we will be using these samples

with sns.plotting_context('poster'):

xx = np.linspace(-6., 6., 100)

plt.plot(xx, n.pdf(xx), label='N(0,1)');

plt.plot(xx, t2.pdf(xx), label = 't_2');

t2samps = t2.rvs(200)

ax = plt.gca()

sns.rugplot(t2samps, ax=ax);

plt.xlim(-6, 6)

plt.legend();

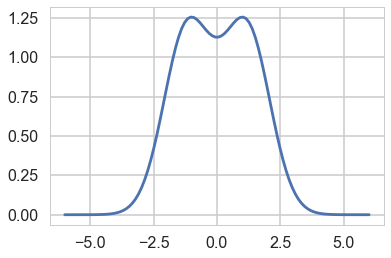

We are interested in finding the $f/g$ for these distributions, since we will want to set $M$ to the supremum of this ratio across the domain we are interested in

fbyg = n.pdf(xx)/t2.pdf(xx)

plt.plot(xx, fbyg);

As you can see, the supremum is achived at two points. Lets get one and thus the $M$.

M = fbyg[np.argmax(fbyg)]

M

1.2569255634535634

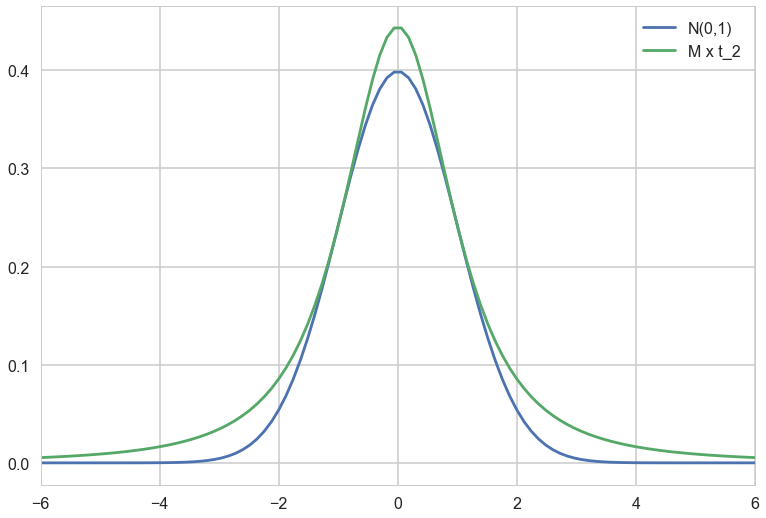

Lets rescale the t by $M$ and plot it so that we can see the majorization.

with sns.plotting_context('poster'):

xx = np.linspace(-6., 6., 100)

plt.plot(xx, n.pdf(xx), label='N(0,1)');

plt.plot(xx, M*t2.pdf(xx), label = 'M x t_2');

plt.xlim(-6, 6)

plt.legend();

Rejection Sampling Implementation

# domain limits

xmin = -6 # the lower limit of our domain

xmax = 6 # the upper limit of our domain

N = 10000 # the total of samples we wish to generate

accepted = 0 # the number of accepted samples

samples = np.zeros(N)

count = 0 # the total count of proposals

outside = 0

f = norm.pdf

g = t2.pdf

# generation loop

while (accepted < N):

while 1:

xproposal = t2.rvs()

if xproposal > xmin and xproposal < xmax:

break

outside+=1

# pick a uniform number on [0, 1)

y = np.random.uniform(0,1)

# Do the accept/reject comparison

if y < f(xproposal)/(M*g(xproposal)):

samples[accepted] = xproposal

accepted += 1

count +=1

print("Count", count, "Accepted", accepted, "Outside", outside)

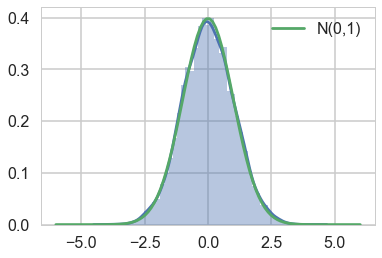

# plot the histogram

sns.distplot(samples);

plt.plot(xx, n.pdf(xx), label='N(0,1)');

# turn on the legend

plt.legend();

Count 12149 Accepted 10000 Outside 307

Notice that the number of rejected samples is roughly 2500. This is because the probability of acceptance is $1/M$.

Expectation values

Lets calculate the expectation value \(E_f[h]\) using the rejection samples obtained.

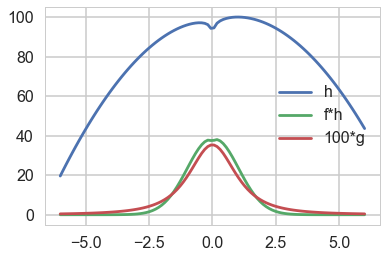

Here is a $h$:

hfun = lambda x: np.log(x**2) - 2*x**2 +2*x +100

plt.plot(xx, hfun(xx), label='h');

plt.plot(xx, f(xx)*hfun(xx), label='f*h');

plt.plot(xx, 100*g(xx), label = '100*g')

plt.legend();

and here is its expectation:

exp_f_of_h = np.mean(hfun(samples))

exp_f_of_h

96.72828784400869

Expectations from Importance Sampling

Remember that in imporance sampling we are calculating

\[E_f[h(x)] = E_g[ \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} h(x)] = E_g[w(x)h(x)]\]where

\[w(x) = f(x)/g(x)\]t2.cdf(6) - t2.cdf(-6), n.cdf(6) - n.cdf(-6)

(0.97332852678457527, 0.9999999980268246)

normer = (t2.cdf(6) - t2.cdf(-6))/(n.cdf(6) - n.cdf(-6))

normer

0.97332852870512321

t2samps = t2.rvs(10300)

t2samps = t2samps[ (t2samps<xmax) & (t2samps>xmin)]

print(t2samps.shape)

fbygfunc = lambda x: (normer*n.pdf(x))/t2.pdf(x)

expec = np.mean(hfun(t2samps)*fbygfunc(t2samps))

expec

(10005,)

96.597949242826999

Some notes on variance

Lets check the “vanilla” monte-carlo variance

vanilla=[]

for k in range(1000):

vm = np.mean(hfun(n.rvs(2000)))

vanilla.append(vm)

np.mean(vanilla), np.std(vanilla)

(96.730847038738176, 0.068037907988511573)

Lets compare the importance sampler’s variance:

eval_is=[]

for k in range(1000):

t2samps = t2.rvs(1000)

t2samps = t2samps[ (t2samps<xmax) & (t2samps>xmin)]

fbygfunc = lambda x: (normer*n.pdf(x))/t2.pdf(x)

expec = np.mean((hfun(t2samps)*fbygfunc(t2samps)))

eval_is.append(expec)

np.mean(eval_is), np.std(eval_is)

(96.774862122671578, 1.0746718309648289)

A different importance sampling estimator

Wow, look at the variance, its really high. An alternative to the standard importance sampling estimator ( $(1/N) \sum_{x_i \sim g} w(x_i) h(x_i)$ ) is the “self normalized” estimator:

\[\frac{\sum_{x_i \sim g} w(x_i) h(x_i)}{\sum_{x_i \sim g} w(x_i)}\]Notice that in the limit $N \to \infty$, the denominator converges to 1 and the entire expectation to out usual case. But in the case of a finite number of samples (and worse for smaller sample sizes), this latter estimator is much more stable, leading to lower variance. Lets try it (we have only 1000 samples)

eval_is=[]

for k in range(1000):

t2samps = t2.rvs(1000)

t2samps = t2samps[ (t2samps<xmax) & (t2samps>xmin)]

fbygfunc = lambda x: (n.pdf(x))/t2.pdf(x)

expec = np.mean((hfun(t2samps)*fbygfunc(t2samps)))

expec = expec/np.mean(fbygfunc(t2samps))

eval_is.append(expec)

np.mean(eval_is), np.std(eval_is)

(96.734905750040383, 0.085451606923249823)

I leave further experimentation, including trying other h and g, to you.