Download Notebook

Contents

- MVN Primer

- Modeling correlation

- Data

- The game

- Definition of Gaussian Process

- Why does it work?

- Levels of Bayes

- Sockeye Salmon example

- Inference

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import scipy as sp

import matplotlib as mpl

import matplotlib.cm as cm

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

pd.set_option('display.width', 500)

pd.set_option('display.max_columns', 100)

pd.set_option('display.notebook_repr_html', True)

import seaborn as sns

sns.set_style("whitegrid")

sns.set_context("poster")

import pymc3 as pm

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

MVN Primer

\[p(x \mid \mu, \Sigma) = (2\pi)^{-n/2}|\Sigma|^{-1/2} \exp\left\{ -\frac{1}{2} (x-\mu)^{T}\Sigma^{-1}(x-\mu) \right\}\]JOINT:

\[p(x,y) = \mathcal{N}\left(\left[{ \begin{array}{c} {\mu_x} \\ {\mu_y} \\ \end{array} }\right], \left[{ \begin{array}{c} {\Sigma_x} & {\Sigma_{xy}} \\ {\Sigma_{xy}^T} & {\Sigma_y} \\ \end{array} }\right]\right)\]MARGINAL:

\[p(x) = \int p(x,y) dy = \mathcal{N}(\mu_x, \Sigma_x)\]CONDITIONAL: \(p(x \mid y) = \mathcal{N}(\mu_x + \Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_y^{-1}(y-\mu_y), \Sigma_x-\Sigma_{xy}\Sigma_y^{-1}\Sigma_{xy}^T)\)

Modeling correlation

General expectation of continuity as you move from one adjacent point to another. In the absence of significant noise, two adjacent points ought to have fairly similar $f$ values.

\[k(x_i, x_j) = \sigma_f^2 exp( \frac{-(x_i-x_j)^2}{2l^2})\]$l$ is correlation length, $\sigma_f^2$ amplitude.

#Correlation Kernel

def exp_kernel(x1,x2, params):

amplitude=params[0]

scale=params[1]

return amplitude * amplitude*np.exp(-((x1-x2)**2) / (2.0*scale))

#Covariance Matrix

covariance = lambda kernel, x1, x2, params: \

np.array([[kernel(xi1, xi2, params) for xi1 in x1] for xi2 in x2])

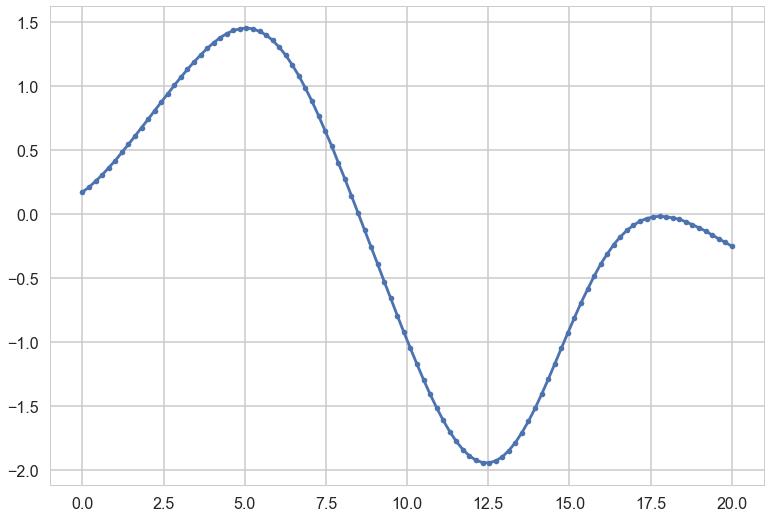

Each curve in plots is generated as:

a = 1.0

nsamps = 100

ell=10

xx = np.linspace(0,20,nsamps)

#Create Covariance Matrix

sigma = covariance(exp_kernel,xx,xx, [a,ell]) + np.eye(nsamps)*1e-06

#Draw samples from a 0-mean gaussian with cov=sigma

samples = np.random.multivariate_normal(np.zeros(nsamps), sigma)

plt.plot(xx, samples, '.-');

The greater the correlation length, the smoother the curve.

We can consider the curve as a point in a multi-dimensional space, a draw from a multivariate gaussian with as many points as points on the curve.

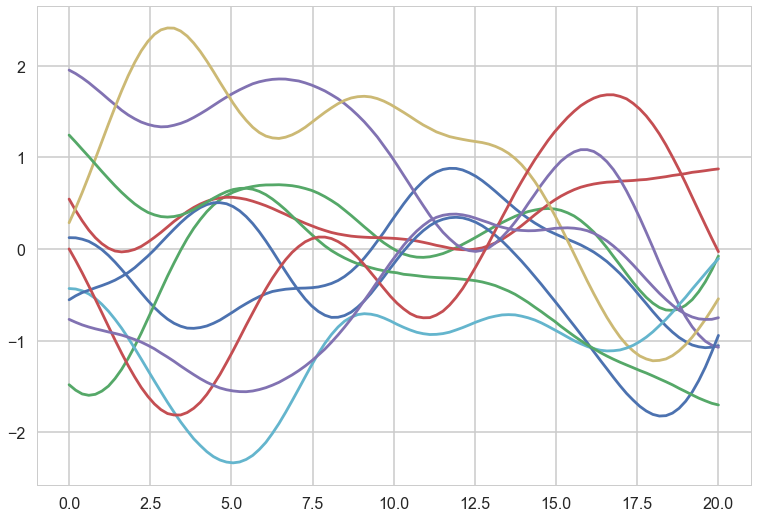

ell = 7.0

a = 1.0

nsamps = 100

x_star = np.linspace(0,20,nsamps)

sigma = covariance(exp_kernel,xx,xx, [a,ell]) + np.eye(nsamps)*1e-06

for i in range(10):

samples = np.random.multivariate_normal(np.zeros(nsamps), sigma)

plt.plot(x_star, samples)

These curves can be thought of as priors in a functional space, all corresponding to some characteristic length scale $l$, which an oracle may have told us.

Data

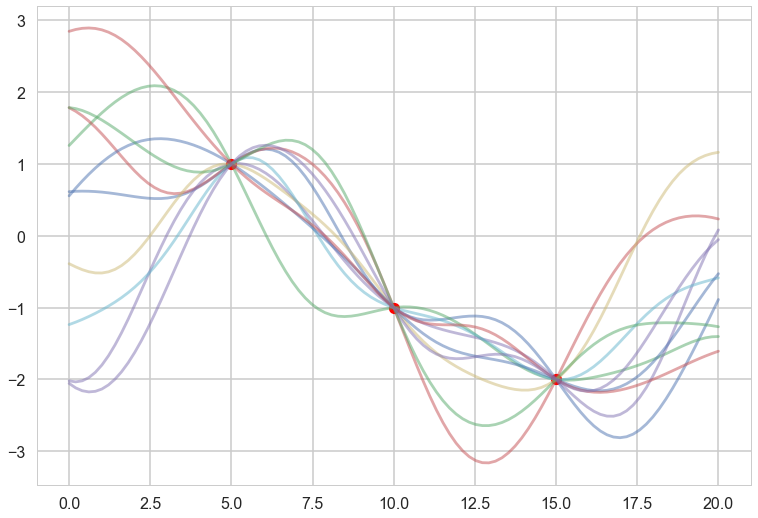

Consider (say 3) data points to have been generated IID from some regression function $f(x)$ (like $w \cdot x$) with some univariate gaussian noise $\sigma^2$ at each point.

The fundamental idea is now to pick curves from the prior which “pass through” these data points, allowing for this $\sigma^2$ noise model

#"test" data

x_star = np.linspace(0,20,nsamps)

# defining the training data

x = np.array([5.0, 10.0, 15.0]) # shape 3

f = np.array([1.0, -1.0, -2.0]).reshape(-1,1)

K = covariance(exp_kernel, x,x,[a,ell])

#shape 3,3

K_star = covariance(exp_kernel,x,x_star,[a,ell])

#shape 50, 3

K_star_star = covariance(exp_kernel, x_star, x_star, [a,ell])

#shape 50,50

K_inv = np.linalg.inv(K)

#shape 3,3

mu_star = np.dot(np.dot(K_star, K_inv),f)

#shape 50

sigma_star = K_star_star - np.dot(np.dot(K_star, K_inv),K_star.T)

#shape 50, 50

plt.plot(x, f, 'o', color="r");

for i in range(10):

samples = np.random.multivariate_normal(mu_star.flatten(), sigma_star)

plt.plot(x_star, samples, alpha=0.5)

plt.plot(x_star, mu_star, '.')

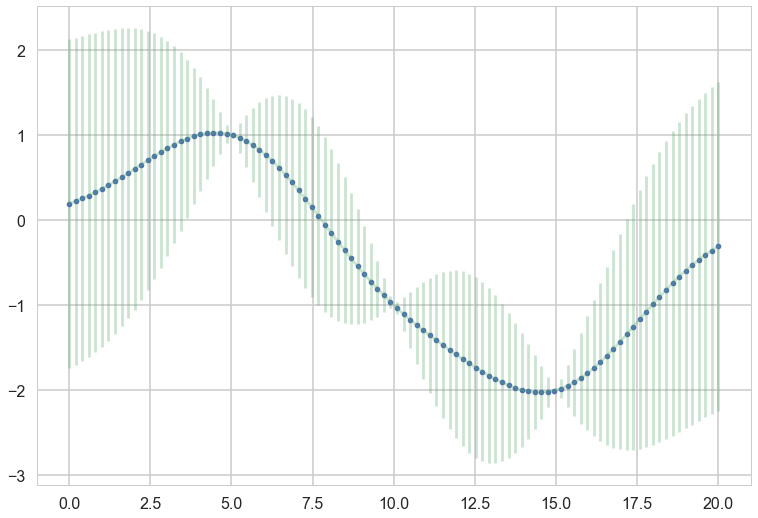

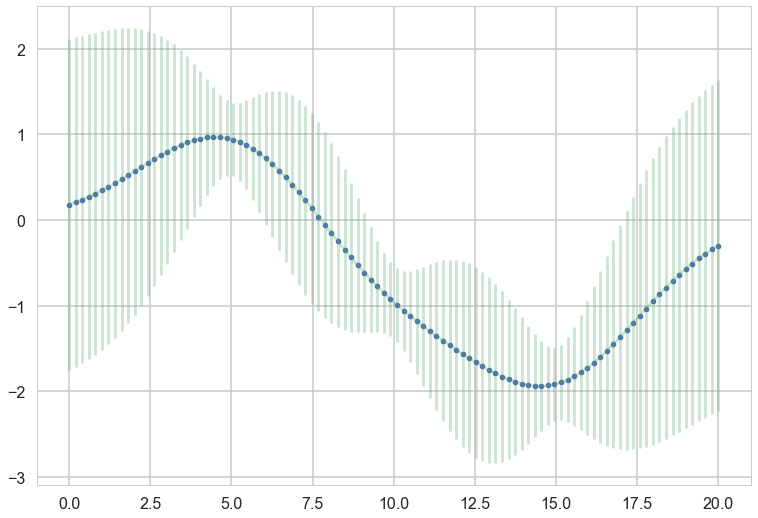

plt.errorbar(x_star, mu_star, yerr=1.96*np.sqrt(sigma_star.diagonal()), alpha=0.3);

sigma_epsilon_sq = 0.05

K_noise = K + np.diag([sigma_epsilon_sq] * K.shape[0])

L = np.linalg.cholesky(K_noise)

#numpy.linalg.solve(a, b)

#Computes the “exact” solution, x, of the well-determined, i.e., full rank, linear matrix equation ax = b.

m = np.linalg.solve(L,f)

alpha = np.linalg.solve(L.T,m)

mu_star_noise_c = np.dot(K_star, alpha)

v = np.linalg.solve(L,K_star.T)

sigma_star_noise_c = K_star_star - np.dot(v.T,v)

plt.plot(x_star, mu_star_noise_c, '.')

plt.errorbar(x_star, mu_star_noise_c, yerr=1.96*np.sqrt(sigma_star_noise_c.diagonal()), alpha=0.3);

The game

How did I pick specific curves from the prior?

Assume that the data and the “prior data” come from a multivariate gaussian, using the MVN formulae from above

JOINT:\(p(f,f^{\infty}) = \mathcal{N}\left(\left[{ \begin{array}{c} {\mu_f} \\ {\mu_{f^{\infty}}} \\ \end{array} }\right], \left[{ \begin{array}{c} {\Sigma_{ff}} & {\Sigma_{ff^{\infty}}} \\ {\Sigma_{ff^{\infty}}^T} & {\Sigma_{f^{\infty}f^{\infty}}} \\ \end{array} }\right]\right) = \mathcal{N}\left(\left[{ \begin{array}{c} {\mu} \\ {\mu_{\infty}} \\ \end{array} }\right], \left[{ \begin{array}{c} K & {K_{\infty}} \\ {K_{\infty}^T} & K_{\infty\infty} \\ \end{array} }\right]\right)\)

MARGINAL: \(\,\,\,\,p(f) = \int p(f, f^{\infty}) df^{\infty} = \mathcal{N}(\mu_{f}, K)\)

where: \(\,\,\,\,K = K(x, x); K_{\infty} = K(x, x^{\infty}); K_{\infty\infty} = K(x^{\infty}, x^{\infty})\)

MARGINAL IS DECOUPLED

…for the marginal of a gaussian, only the covariance of the block of the matrix involving the unmarginalized dimensions matters! Thus “if you ask only for the properties of the function (you are fitting to the data) at a finite number of points, then inference in the Gaussian process will give you the same answer if you ignore the infinitely many other points, as if you would have taken them all into account!” -Rasmunnsen

Game Part 2

Conditional

\[p(f^{*} \mid y) = \mathcal{N}\left(\mu_{*} + K_{*}(K + \sigma^2 I)^{-1}(y-\mu), \,\, K_{**}-K_{*}(K + \sigma^2 I)^{-1}K_{*}^T \right)\]EQUALS Predictive

Definition of Gaussian Process

Assume we have this function vector $ f=(f(x_1),…f(x_n))$. If, for ANY choice of input points, $(x_1,…,x_n)$, the marginal distribution over $f$:

$P(F) = \int_{f \not\in F} P(f) df$

is multi-variate Gaussian, then the distribution $P(f)$ over the function $f$ is said to be a Gaussian Process.

We write a Gaussian Process thus:

$f(x) \sim \mathcal{GP}(m(x), k(x,x\prime))$

where the mean and covariance functions can be thought of as the infinite dimensional mean vector and covariance matrix respectively.

a Gaussian Process defines a prior distribution over functions!

Once we have seen some data, this prior can be converted to a posterior over functions, thus restricting the set of functions that we can use based on the data.

Since the size of the “other” block of the matrix does not matter, we can do inference from a finite set of points.

Any $m$ observations in an arbitrary data set, $y = {y_1,…,y_n=m}$ can always be represented as a single point sampled from some $m$-variate Gaussian distribution. Thus, we can work backwards to ‘partner’ a GP with a data set, by marginalizing over the infinitely-many variables that we are not interested in, or have not observed.

GP regression

Using a Gaussian process as a prior for our model, and a Gaussian as our data likelihood, then we can construct a Gaussian process posterior.

| Likelihood: $$y | f(x),x \sim \mathcal{N}(f(x), \sigma^2I) $$ |

where the infinite $f(x)$ takes the place of the parameters.

Prior: $f(x) \sim \mathcal{GP}(m(x)=0, k(x,x\prime))$

| Infinite normal posterior process: $f(x) | y \sim \mathcal{GP}(m_{post}, \kappa_{post}(x,x\prime)).$ |

The posterior distribution for f is:

\[\begin{aligned} m_{post} &= k(x\prime,x)[k(x,x) + \sigma^2I]^{-1}y \\ k_{post}(x,x\prime) &= k(x\prime,x\prime) - k(x\prime, x)[k(x,x) + \sigma^2I]^{-1}k(x,x\prime) \end{aligned}\]Posterior predictive distribution for $f(x_)$ for a test vector input $x_$, given a training set X with values y for the GP is:

\[\begin{aligned} m_* &= k(x_*,X)[k(X^T,X) + \sigma^2I]^{-1}y \\ k_* &= k(x_*,x_*) - k(x_*,X^T)[k(X^T,X) + \sigma^2I]^{-1}k(X^T,x_*) \end{aligned}\]The predictive distribution of test targets y∗ : add $\sigma^2 I$ to$k_*$$.

Why does it work?

Infinite basis sets and Mercer’s theorem

Now consider an infinite set of \(\phi(x)\). Like a fourier series or a Bessel series.

We can construct an infinitely parametric model.

This is called a non-parametric model.

We just need to be able to define a finite kernel \(\kappa(x,x') = \psi(x)^T \psi(x')\)!!

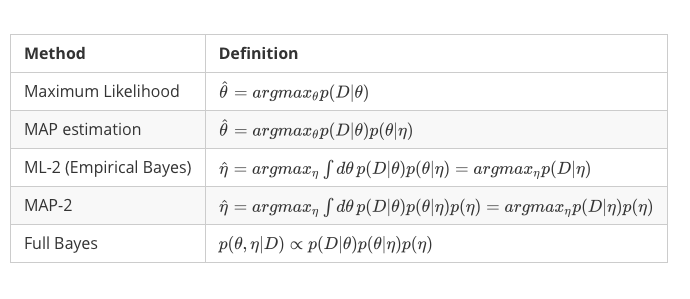

Levels of Bayes

We shall here only show full bayes using the likelihood marginalized in function space.

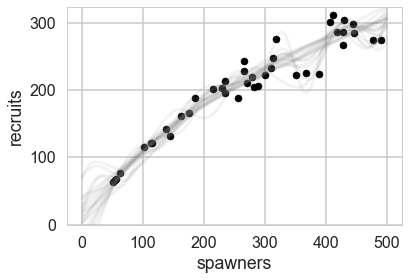

Sockeye Salmon example

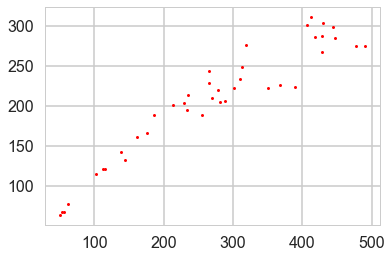

Munch, Kottas and Mangel (Bayesian nonparametric analysis of stock- recruitment relationships. Canadian Journal o f Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 62:1808–1821, 2005.) use Gaussian process priors to infer stock-recruitment (SR ) functions for various fish. We concentrate here on Sockeye Salmon. SR functions relate the size of a fish stock to the number or biomass of recruits to the fishery each year. The authors argue that GP priors make sense to use since model uncertainty is high in Stock Recruitment theory.

!cat data/salmon.txt

year recruits spawners

1 68 56

2 77 62

3 299 445

4 220 279

5 142 138

6 287 428

7 276 319

8 115 102

9 64 51

10 206 289

11 222 351

12 205 282

13 233 310

14 228 266

15 188 256

16 132 144

17 285 447

18 188 186

19 224 389

20 121 113

21 311 412

22 166 176

23 248 313

24 161 162

25 226 368

26 67 54

27 201 214

28 267 429

29 121 115

30 301 407

31 244 265

32 222 301

33 195 234

34 203 229

35 210 270

36 275 478

37 286 419

38 275 490

39 304 430

40 214 235

df = pd.read_csv("data/salmon.txt", sep="\s+")

df.head()

| year | recruits | spawners | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 68 | 56 |

| 1 | 2 | 77 | 62 |

| 2 | 3 | 299 | 445 |

| 3 | 4 | 220 | 279 |

| 4 | 5 | 142 | 138 |

plt.plot(df.spawners, df.recruits, 'r.', markersize=6, label=u'Observations');

Inference

Use the marginal likelihood:

\[p(y|X) = \int_f p(y|f,X)p(f|X) df\]The Marginal likelihood given a GP prior and a gaussian likelihood is:

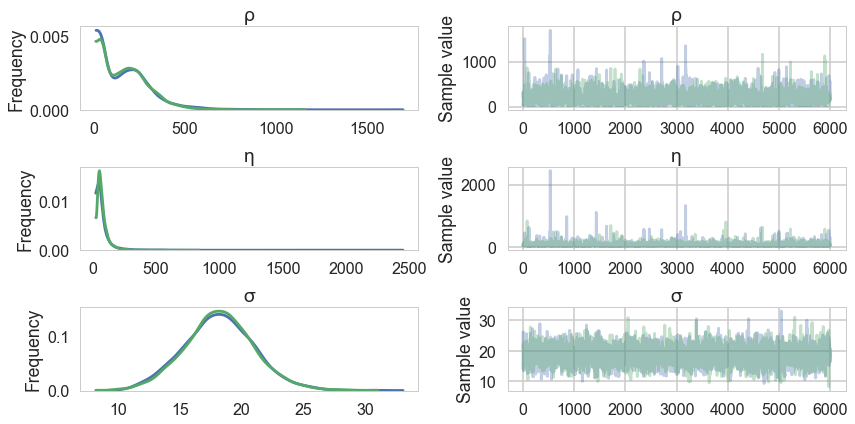

\[\log p(y|X) = - \frac{n}{2}\log2\pi - \frac{1}{2}\log|K + \sigma^2I| - \frac{1}{2}y^T(K+\sigma^2I)^{-1}y\]#taken from fonnesbeck

with pm.Model() as model:

# Lengthscale

ρ = pm.HalfCauchy('ρ', 1)

η = pm.HalfCauchy('η', 1)

M = pm.gp.mean.Linear(coeffs=(df.recruits.values/df.spawners.values).mean())

K = (η**2) * pm.gp.cov.ExpQuad(1, ρ)

σ = pm.HalfCauchy('σ', 1)

recruit_gp = pm.gp.Marginal(mean_func=M, cov_func=K)

recruit_gp.marginal_likelihood('recruits', X=df.spawners.values.reshape(-1,1),

y=df.recruits.values, noise=σ)

with model:

salmon_trace = pm.sample(10000)

Auto-assigning NUTS sampler...

Initializing NUTS using jitter+adapt_diag...

Multiprocess sampling (2 chains in 2 jobs)

NUTS: [σ_log__, η_log__, ρ_log__]

100%|██████████| 10500/10500 [02:49<00:00, 61.95it/s]

The number of effective samples is smaller than 25% for some parameters.

salmon_trace = salmon_trace[4000:]

pm.traceplot(salmon_trace, varnames=['ρ', 'η', 'σ']);

X_pred = np.linspace(0, 500, 100).reshape(-1, 1)

with model:

salmon_pred = recruit_gp.conditional("salmon_pred2", X_pred)

salmon_samples = pm.sample_ppc(salmon_trace, vars=[salmon_pred], samples=20)

100%|██████████| 20/20 [00:00<00:00, 26.23it/s]

ax = df.plot.scatter(x='spawners', y='recruits', c='k', s=50)

ax.set_ylim(0, None)

for x in salmon_samples['salmon_pred2']:

ax.plot(X_pred, x, "gray", alpha=0.1);

Exercise

We might be interested in what may happen if the population gets very large – say, 600 or 800 spawners. We can predict this, though it goes well outside the range of data that we have observed. Generate predictions from the posterior predictive distribution (via conditional) that covers this range of spawners.

# Write answer here